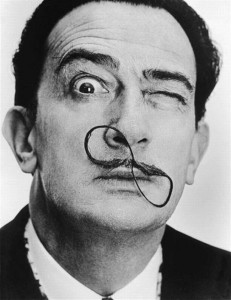

Salvador Dali isn’t exactly known for his subtlety. His large ego was only surpassed — and certainly supported — by his wild creativity, which showed us a (very) different way(s) to look at the world.

We can look to his paintings and try to piece together the man and the myth that comprises Dali. Take for instance, his portrait of his dead brother, aptly titled “Portrait of My Dead Brother.”

Because we are talking about Dali, this portrait is not simply a portrait, and Dali is front and center here, too.

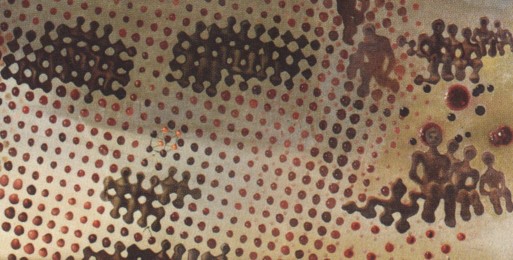

A face emerges in the middle of the canvas, as dots coalesce to form the facial features of a young boy, presumably his brother. His brother died as a toddler, nine months before Dali was born, and Dali shared his first name with both his father and dead brother.

This connection seemed to haunt Dali; he was born into the shadow of grief.

You can just make out the dark and light cherries connecting as molecules above the nostrils.

(Credit: wikiart.org)

Light and shadow play out in this painting. Looking closer, we see cherries; the pop-art-like dots that give rise to the face that stares back at us are cherries. The cherries molecularly form the features of Dali and his brother; lighter red cherries descend from above, or heaven, and darker brownish cherries ascend from the ground, the earth, connecting at a point just above the nostrils.

These two forces, light from above and darkness from below, form the composite image of Dali’s face and that of his brother.

This may seem inverted, since we often associate the ethereal heavens with those we have lost, and the earth with the muddied, physical presence of the living. But Dali considered himself divine…so, there you go; our Dali is The Salvador that comes from the heavens.

As Dali himself stated, “Every day, I kill the image of my poor brother. . . I assassinate him regularly, for the ‘Divine Dali’ cannot have anything in common with this former terrestrial being.”

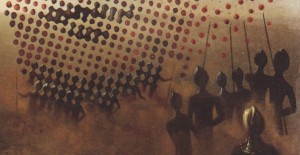

To assassinate his brother in this instance, Dali has enlisted an army. Some of the cherried dots either lose or gain form as men of war that march across the lower right quadrant of the painting.

Spears in hand, they seem to be fighting off the cherries, or are protecting them. It is hard to tell the difference. The war-like figures in the center of the painting become the darker cherries that ascend towards the heavenly Dali force — the shadow appears to be winning if taken by mass alone.

Various shapes across the visual field hint at other bodies, worldly and otherworldly. Those with feet planted in the ground settle into positions of giving or receiving solace when not at war.

Reading this portrait becomes a dizzying experience. It shifts and spirals as it forms some sort of twisted storyline that emerges only to fall back in on itself, much like life itself.

Saving Face

Saving Face

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“The Sea” by John Banville

“The Sea” by John Banville

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento